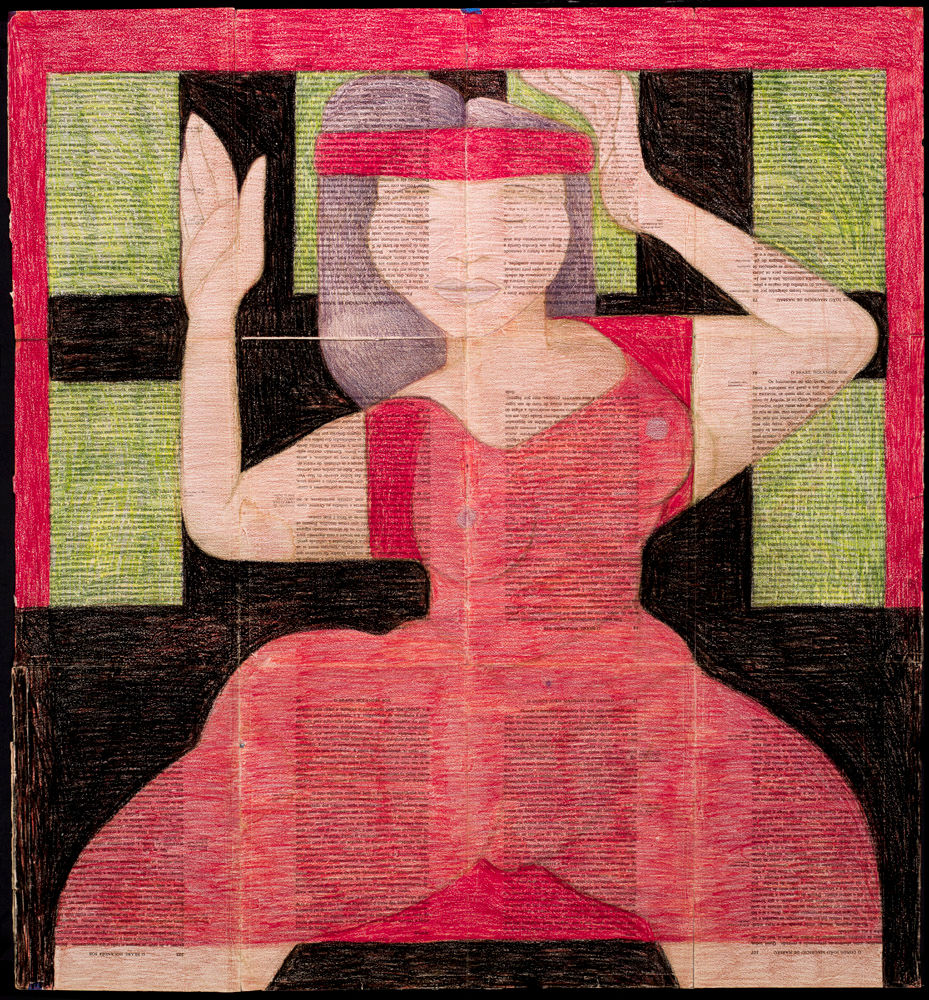

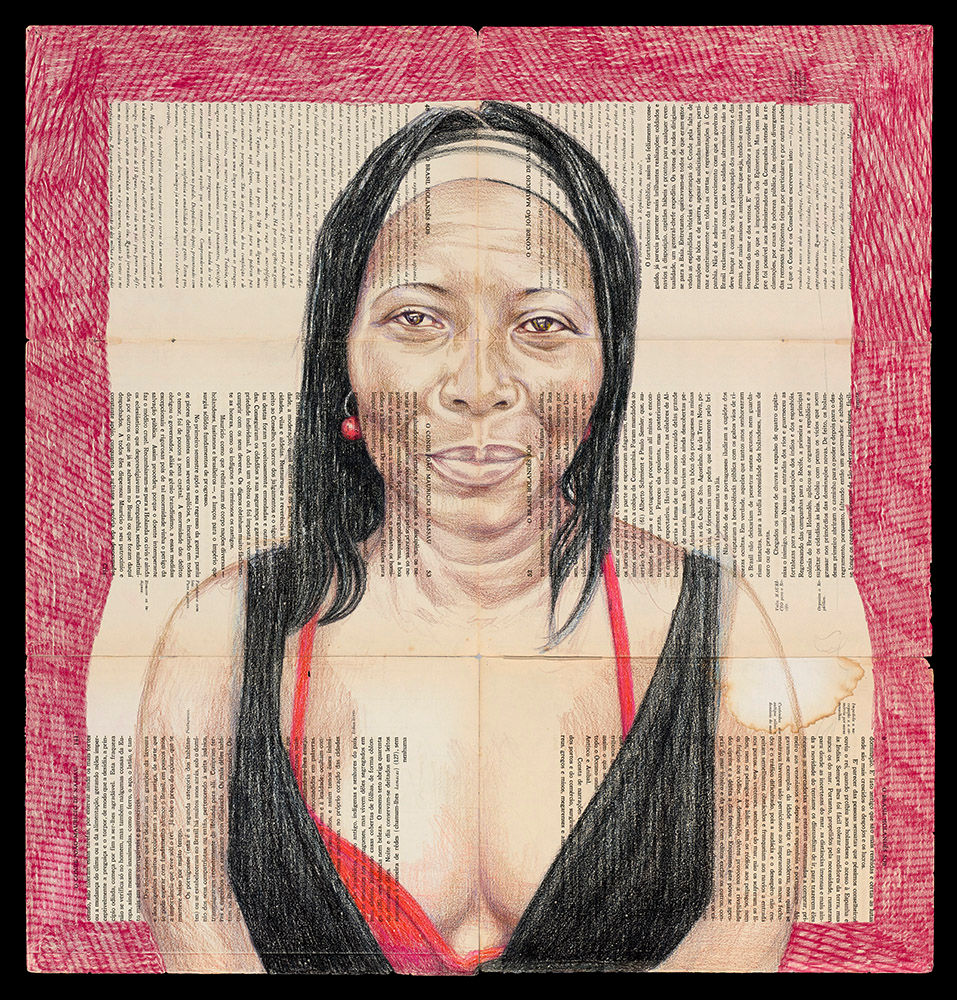

J Michael Walker

"Pages from a Bahia Diary" 2011 - Present

An ongoing series,

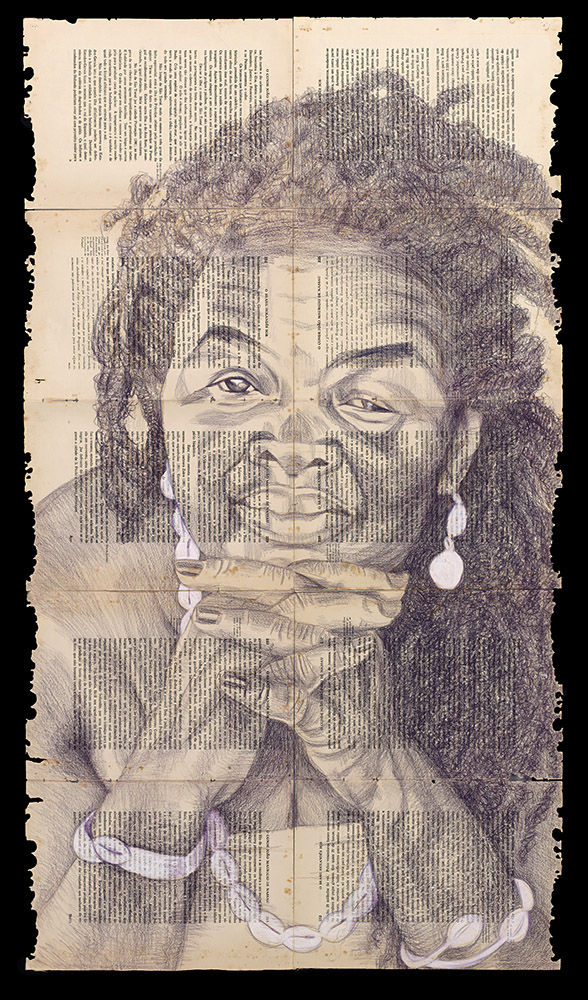

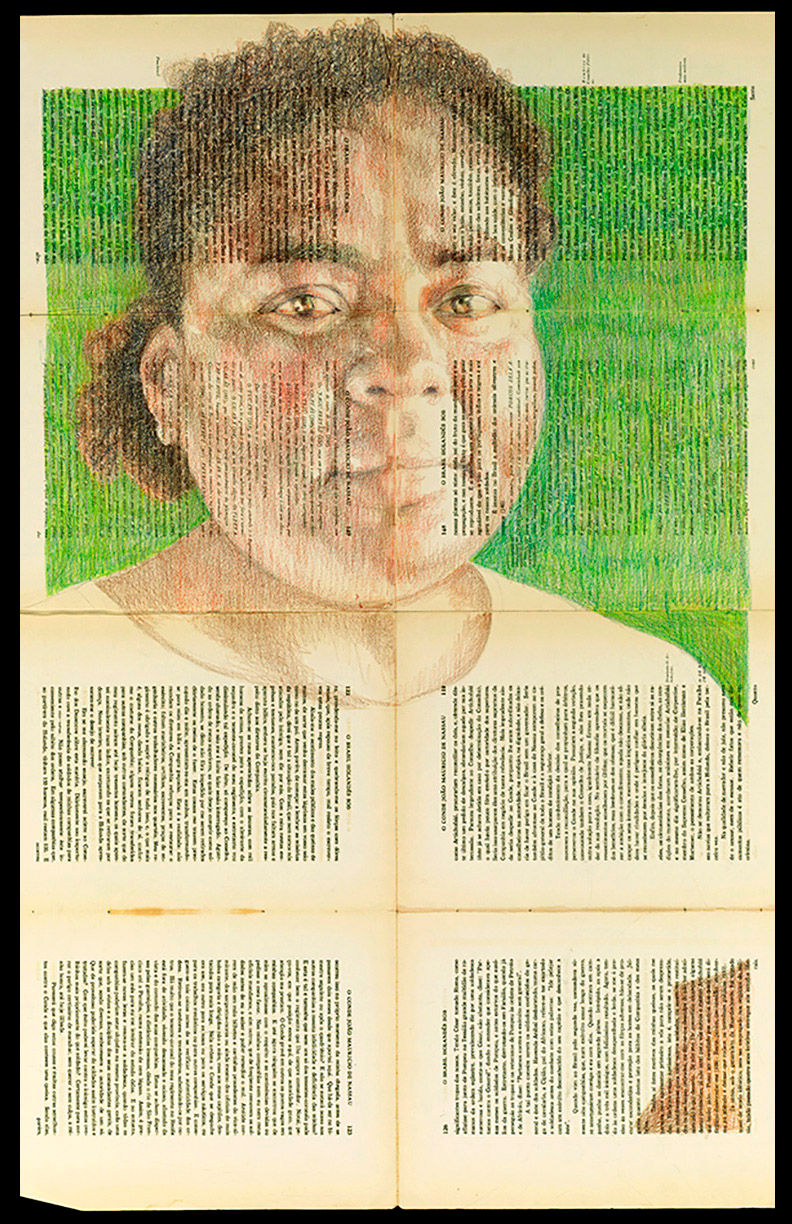

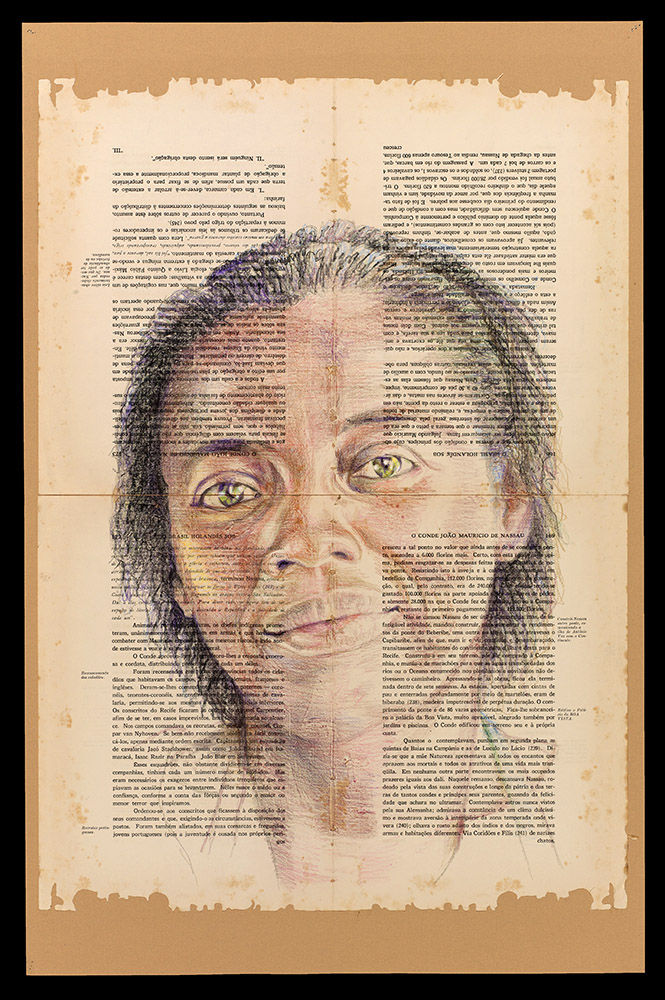

"Pages from a Bahia Diary" is a suite of responsorial psalms; a story of unintended consequences and extraordinary, ultimately joyful, perseverance; where foreground converses with background; and where "now" talks back to "then," resulting in a "corrected text" by giving the descendants of the enslaved the final word.

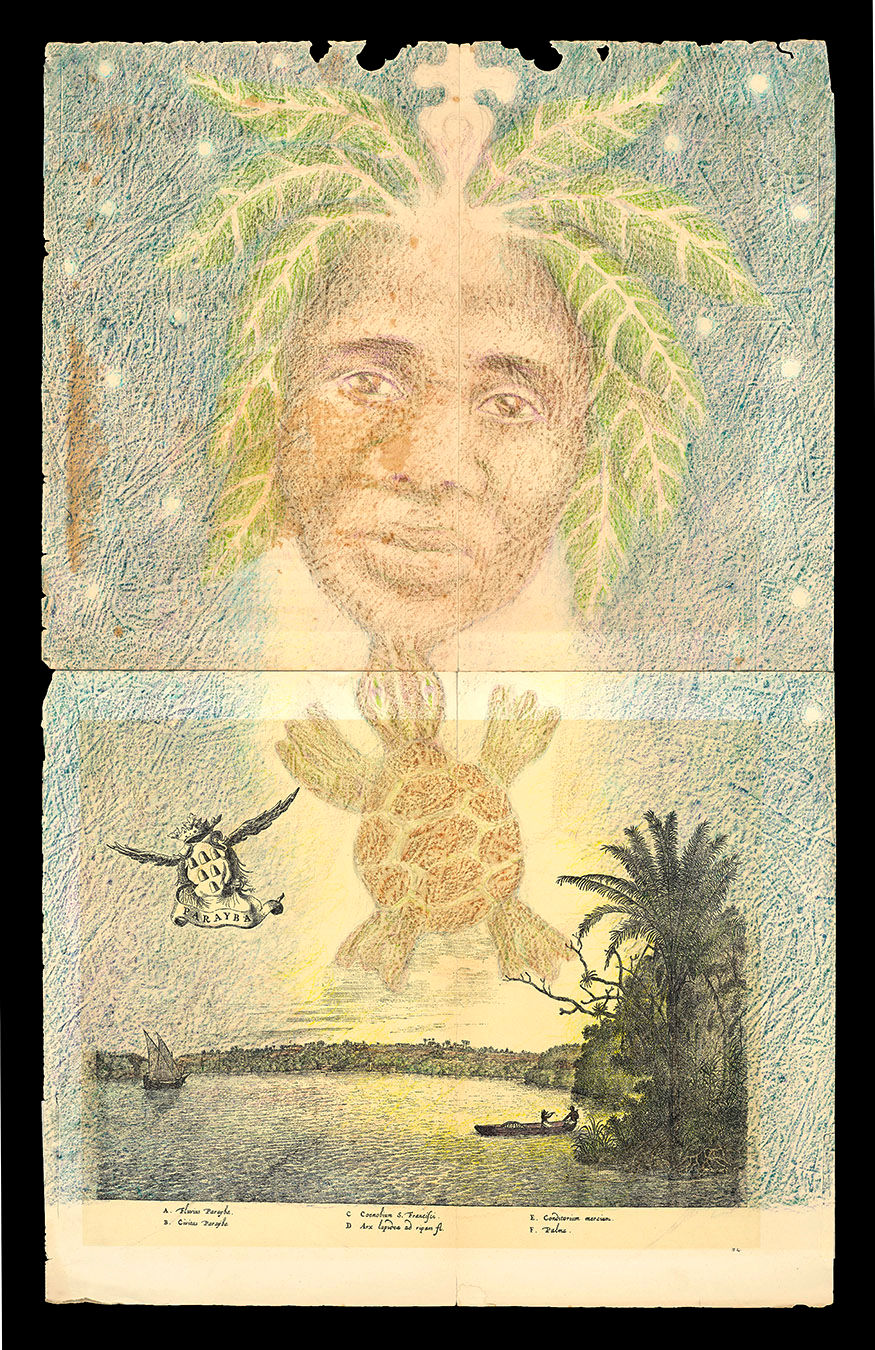

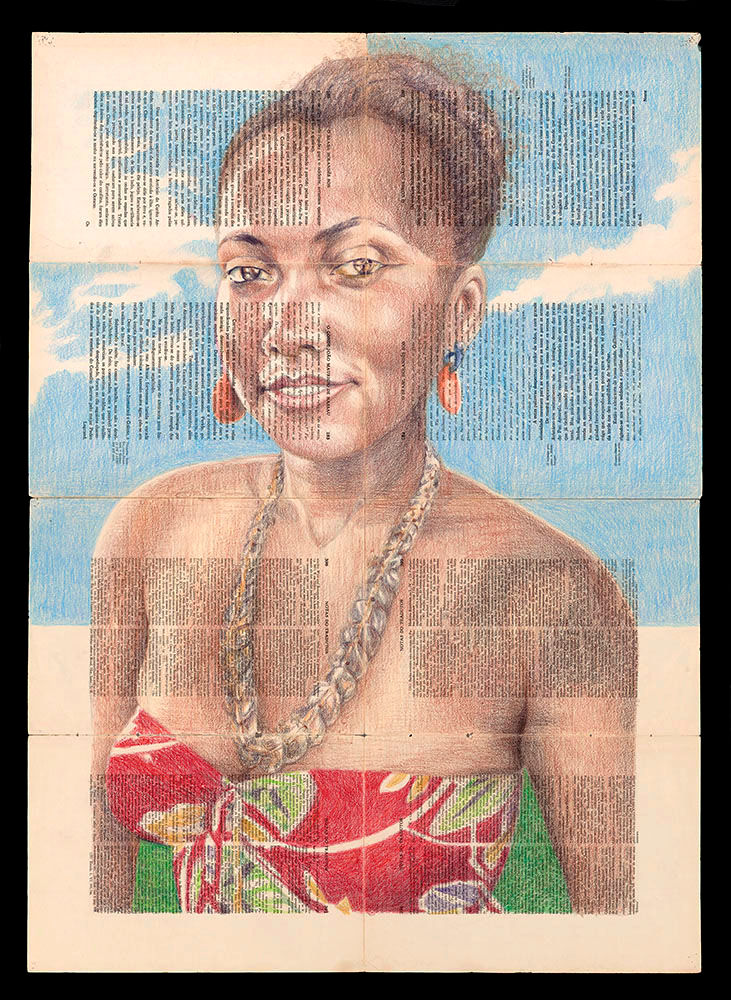

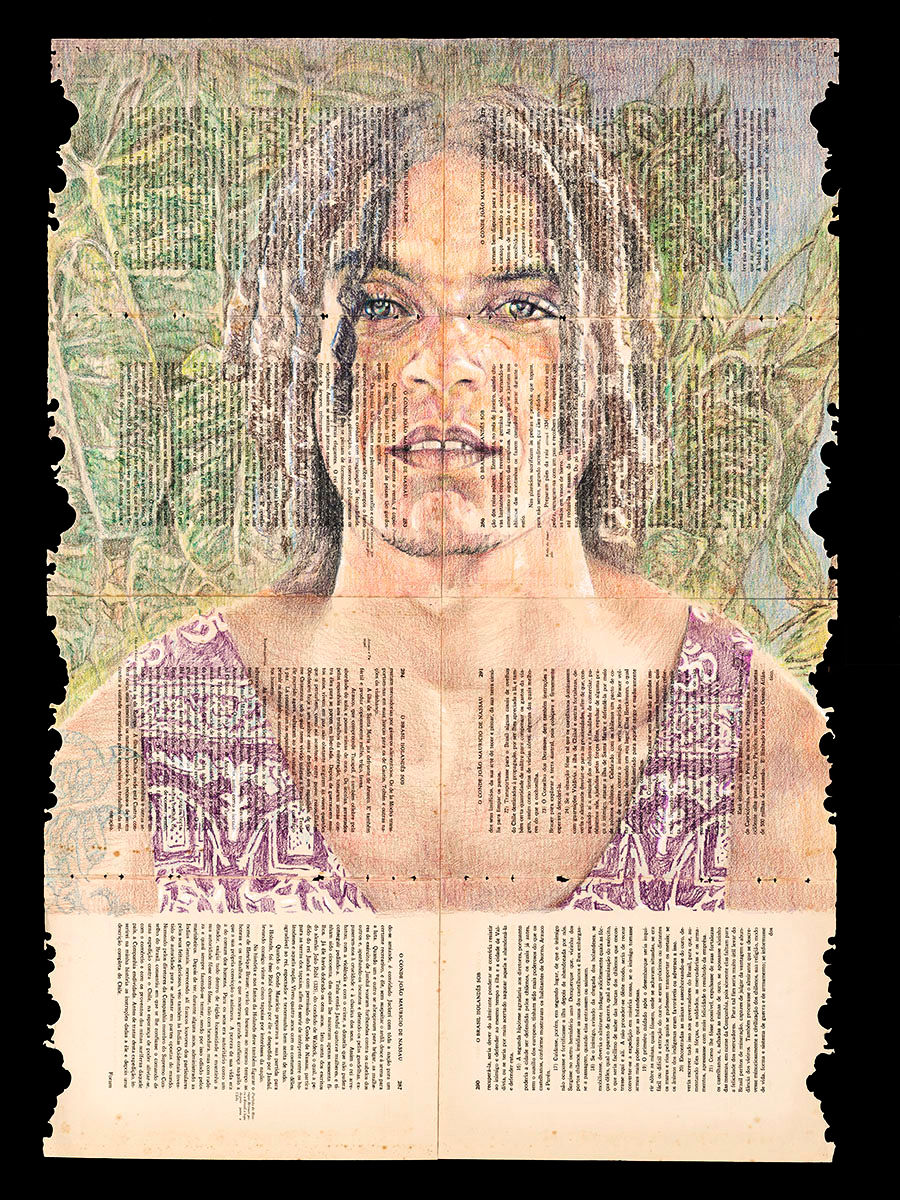

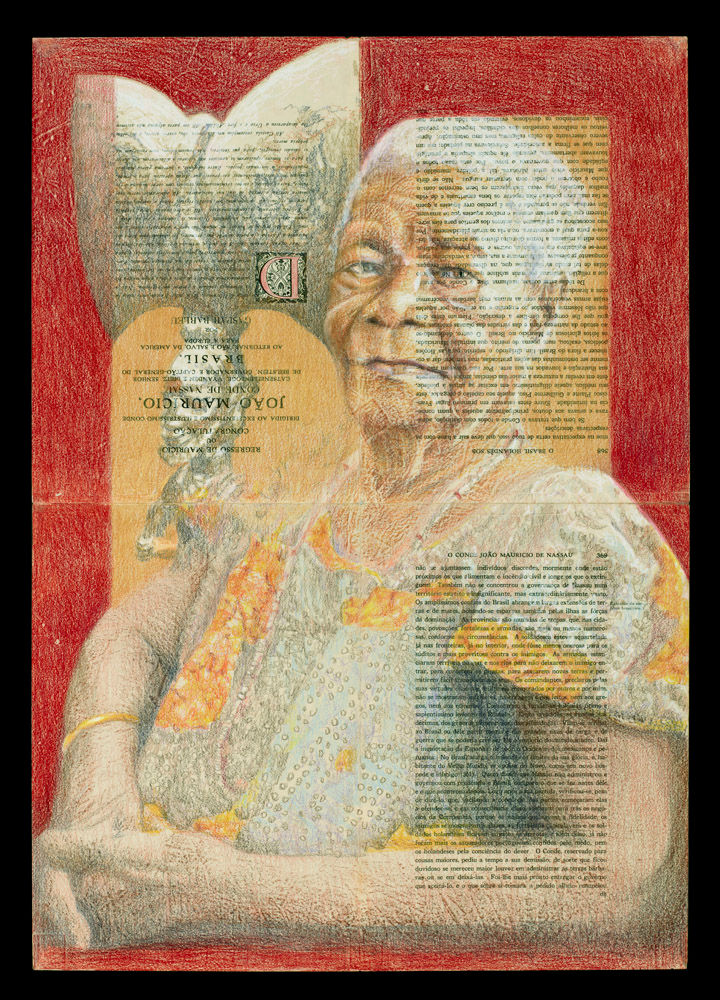

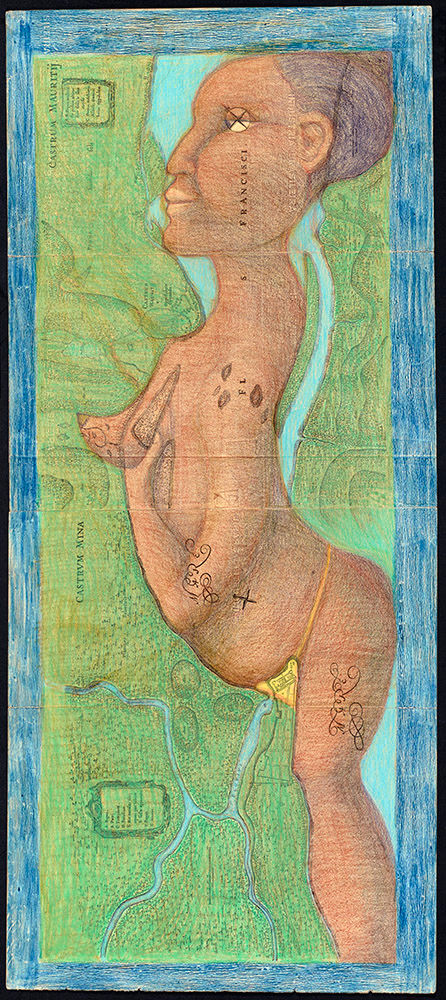

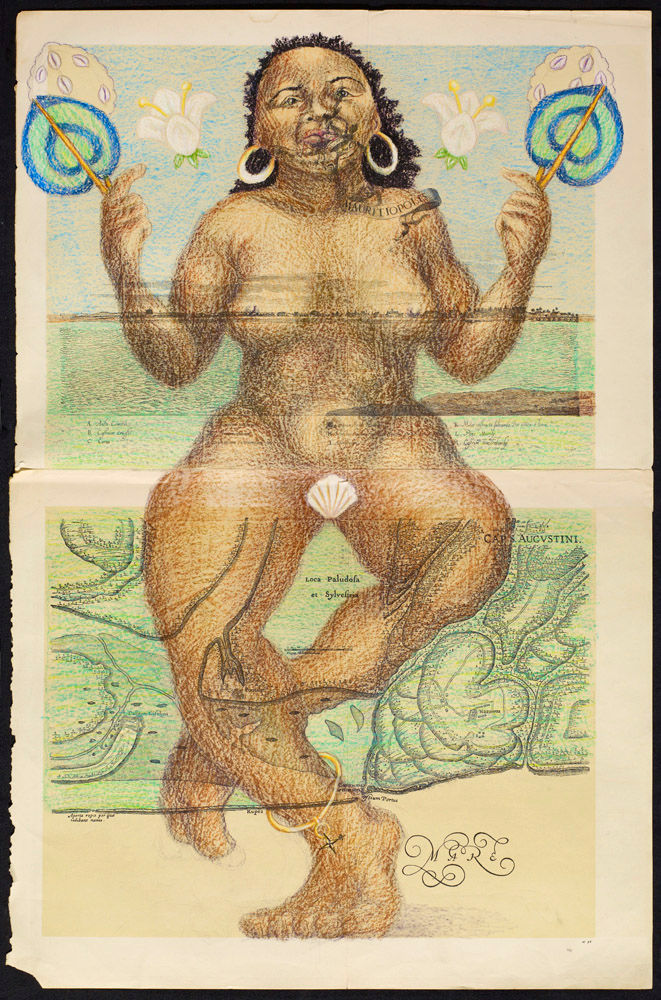

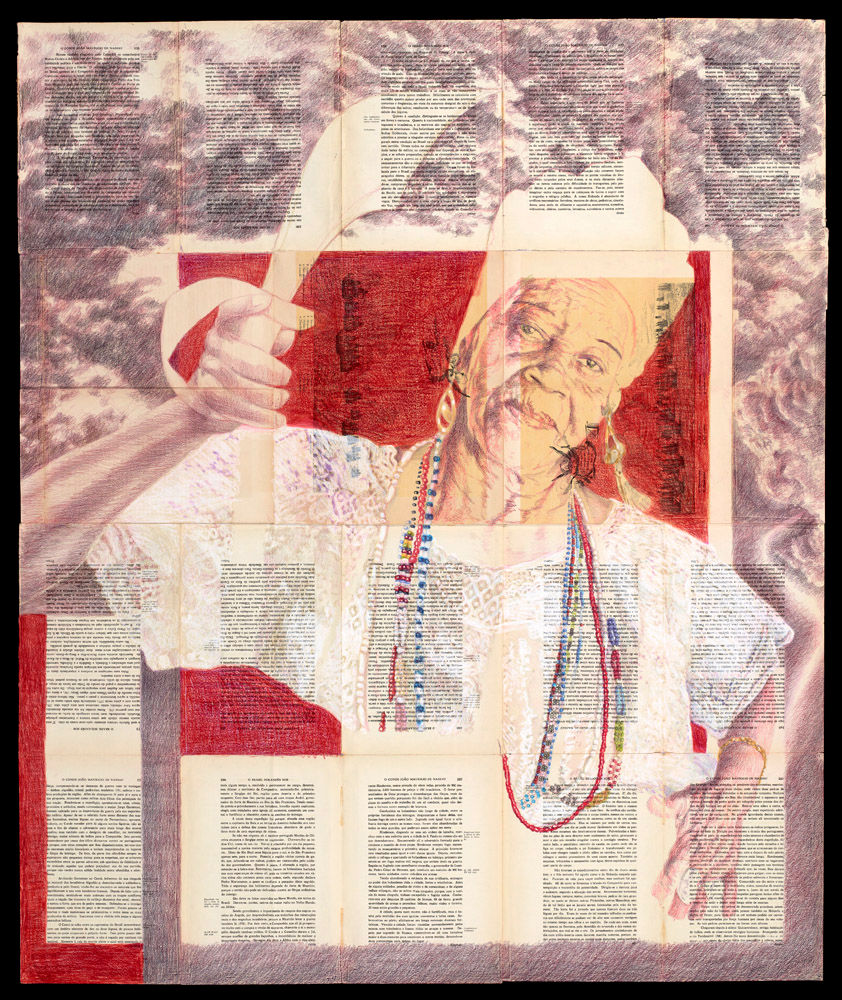

My portraits of Afro-Bahian women and their orishas are drawn and painted directly on the pages of the limited 1940 folio edition of "Historia dos feitos recien praticados," by Gaspar Barleu (Caspar Barlaeus), an important 17th century laudatory account of the Dutch colonial empire of Brazil, under the gpvernorship of Count Johan Maurits.

In these artworks, descendants of the enslaved Africans seized, brutalized, and imported from Africa’s Gold Coast like cargo, and ruled over by, alternately, the Dutch and the Portuguese colonial powers, emerge from and assume power over that history of enslavement and colonization.

Unlike traditional narratives of freedom,

which center unique heroes in epic pose, I honor women (and occasionally men) one might encounter – as I have – in neighborhoods, on back roads and street corners, in villages and Candomblé temples, whose vibrant culture is - despite the intentions, brutal rule, and power of the European colonial powers - the continuing reason people visit and gravitate to Bahía.

I acquired my first copy of Barleu’s book – disbound torn and ragged – around 1993, attracted to its appearance, but unaware of its contents; moved by the vague idea – as artists often do – “someday I’ll figure out what to do with this.”

In 2011, I was awarded a fellowship from the Sacatar Institute, to ravel to its artist residency in Bahia, Brazil, where I intended to create a project – in Baia de Todos os Santos – similar to the “All the Saints of the City of the Angels” project I had recently completed about Los Angeles, California, , where I live.

As I packed art materials for my trip, my eyes fell on that tattered book I'd bought years earlier;

I read "BRASIL" on its title page; thought "That's where I'm going"; and tossed it into my luggage.

Arriving at the residency on the island of Itaparica in Bahia, however, I unexpectedly found myself wading through Yoruba spirits I knew nothing about, but which were as palpable and real to me as the Atlantic waves lapping the shore outside my studio windows. (The Yoruba spiritual culture of West Africa arrived with many of the over 2 million enslaved Africans who survived the journey to Bahia’s port; indeed, it is perhaps the most significant force that has enabled their descendants to endure and thrive).

Almost immediately after arriving in Itaparica, I drew my first portrait of a Bahiana over several pages of Barleu’s text. When the nature of that text was explained to me, I understood how my inuition nearly twenty years earlier had set the course, planted a seed free of my recognition.

Thus I had begun creating, as I continued ot meet and photograph women in the community around the artist residency, a theatre for these Afro-Brazilian women to assert themselves over and against Barleu’s words and Maurits’ deeds.

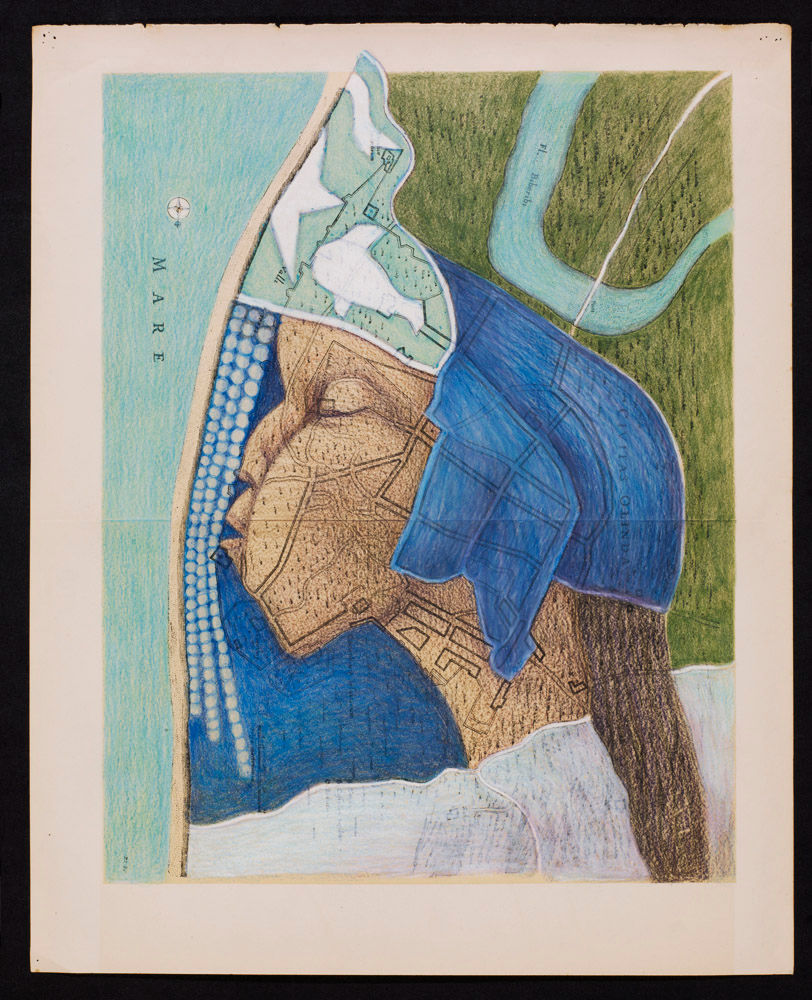

“Historia dos feitos” was a beautifully printed folio-sized edition (only 500 copies, on laid paper), and it includes 56 fold-out maps and seascapes of Brazil. Besides portraying my new AFro-Brazilian friends on collaged pages of the text, I began to intuit, in the maps, images of the orishas – the Yoruba spiritual guides who accompanied the enslaved and who similarly had to accommodate themselves in this new landscape, which the maps would make evident.

No one in Bahia has ever been surprised that a book I bought 20 years before coming there would prove so uniquely appropriate. Candomblé teaches that we are each born with a destiny to fulfill: “Of course,” Bahians say to me, “the book was waiting for you to come.”

I’ve now created over 50 artworks inspired by my immersion in Itaparica and the Yoruba spirituality that animates the island.

In June 2022, I was invited back to Sacatar, where I reconnected with a number of my friends from 11 years ago, and gifted the women whose portraits I’ve created, large frameable prints of their portraits;. This exchange deepened my connection with the community, already grateful for my mural of their patron saint, San Antonio des Navegantes, on the exterior wall of their church.

As two of the women told me,

“You have to come back: you’re from here now.”

Asé.